“Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore.” Joe Biden, 2020

As a non-Ph.D. economist, it would be entirely disingenuous to imply I have some better and deeper understanding of inflation than many experts who study this their whole lives. But, I have often remarked that predicting inflation is super complex, and my only commentary was not to fix what was not broken and to not be governed by the post-GFC mentality.

Back in the 1970s, Arthur Burns believed inflation was less to do with monetary dynamics and more that powerful corporations and labor unions caused “cost-push” inflation, and a part of this theory led him to believe ideas like wage and price controls could prove valuable – which they did not. He also faced significant political pressures given his close relationship with Nixon and allegedly/likely factored elections into his calculus. He had to manage through the supply shock of the Arab Oil Embargo. We still operated with the Phillips Curve as a key determinant of inflation outcomes and a natural rate of employment concept (the level that does not create inflation pressures). Still, for much of the 1970s, Burns – who had material economics bonafides – was operating in a world of complexity he either only partially understood or understood the phenomenon completely but was lacking in resolve to accept the consequences. The “Stop Go” periods, where he would tighten and then quickly pivot when signs of employment losses and recession would rear their head, was later described as one of the catalysts for inflationary psychology.

As Ben Bernanke writes in his recent 21st Century Monetary Policy book, “over one stretch in the 1970s, CPI inflation swung wildly from 3.4% in 1972 to 12.3% in 1974 to 4.9% in 1976, then back to 9.0% in 1978…the combination of oil price shocks and destabilized inflation expectations was powerful. Inflation seemed increasingly out of control, reaching 13.3% in 1979 and 12.5% in 1980.” Looking at the so-called “Great inflation” episode of the 1960s and 1970s, it becomes obvious that, like today, there is no shortage of theories about how it came to pass. Most would argue it was guns and butter of the 1960s that got the ball rolling, aided by closing the gold window, ineffective wage/price controls, the supply shock of the oil crisis (which, like other supply shocks, is stagflationary), and then highly erratic policy and overly focused on the wrong key drivers that helped create the perfect storm.

In 1978, President Carter ushered in the Humphrey Hawkins Act (aka Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act), which amplified the idea that the Fed (and others in government) could easily twist a few knobs like a music producer/engineer to get the desired result, when in fact they cannot. Milton Friedman’s brilliance was that he could cut through a lot of noise. He mentioned that excessive monetary growth would be like a hard night out of drinking: it would feel good but cause a nasty hangover – inflation. Paul Volcker was the person who sliced through the debates and realized that the way forward was to rid the system of one of the drivers of inflation (excessive monetary growth) but of psychology as well. Taking an economy through deep downturns to prove it meant business was what was required. For those that don’t remember it, there was no shortage of political mudslinging back then. But, Reagan realized that to propel the country forward, the inflation nuisance needed to be slain, and he let Volcker do his thing. I don’t recall reading stories like the one where Lyndon Johnson beat up William McChesney Martin at his Texas ranch to raise rates and deprive him of dollars while soldiers were dying in Vietnam.

Fast forward to today. For starters, let’s look at the quote above. What does Biden mean? I am not 100% certain, but there has, for quite some time, been an undercurrent (“trumped up trickle down economics’ ‘) that Reagan policy effectiveness was overstated and caused both excessive financialization and inequality. Even though Clinton and Obama believed in or were influenced by Reagan’s policies (who was influenced by Friedman), Biden and others on the left felt it was time to remove those shackles. So, when I read through something coined as the “Inflation Reduction Act,” which nobody seriously thinks will move the needle on inflation one way or the other but will certainly involve more spending, or have Elizabeth Warren continue to bang on about how fighting inflation may have costs in jobs, (including those in the incumbent party) or even Powell suggesting that 2.5% was neutral (Bill Ackman had a great tweet noting that “neutral is to rate as transitory is to inflation”), it still does not seem as if influential actors are trying to get inflation under control in a coherent effort, or even that it should. Real fiscal action on inflation would not have CoVid-related policies like delaying student loan repayments still in place (estimated to cost the taxpayers close to $200B) and float ideas about canceling debt altogether.

Luis Zingales at the University of Chicago remarked on his podcast that Friedman’s “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” should be replaced with “inflation is always and everywhere a political phenomenon.”

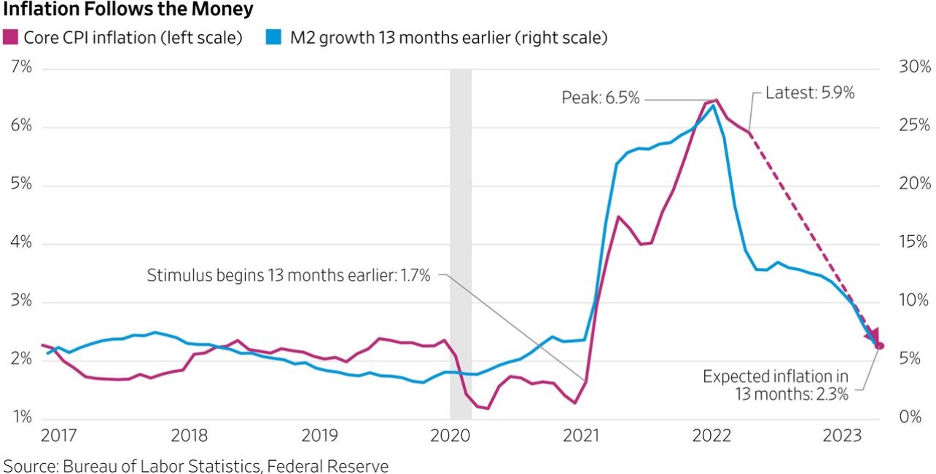

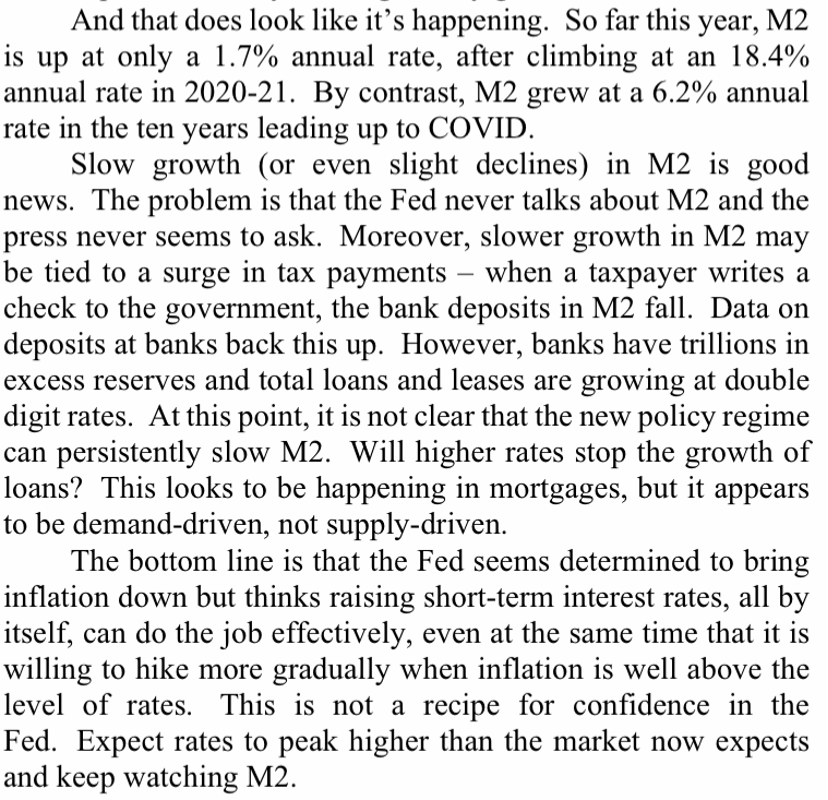

On the monetary side, Donald Luskin has a good point about M2 monetary growth, as it has slowed considerably and is now below pre-pandemic levels (usually 6% growth) at around 1.7%, And, if in fact, inflation was only about money growth and not about inflation psychology, that would be a reasonable argument. Jeremy Siegel at Wharton has been making similar arguments.

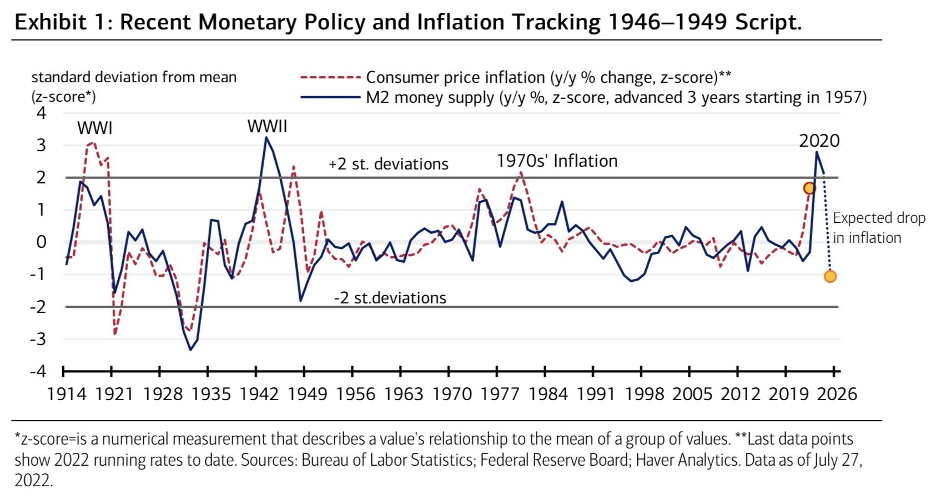

There is a historical precedent for such a fall in material monetary growth, and that was post-WWII.

Here is commentary from Brian Wesbury of First Trust – who I know from my Chicago days and is a great economist talking about reduced M2 growth.

I wrote previously about the historical mindset about public debt, referencing Barry Eichenberg’s book at the time. It was raised to fight wars generally, and the rate of pay down varied, but it was paid down. It helped that behind the scenes was the gold standard, working to ensure purchasing power didn’t veer all that much from the government’s actions. And while post-WWII had a lot of debt to service and the country had challenges, it also had the greenfield opportunity of having won a war, social cohesion, and productive capacity to export to areas torn by war. By the 1960s and 1970s, much had changed or was in the process of changing. The best way to articulate the 1940s to 1970’s difference is rationing during the war versus waiting in lines to get gas (by license plate number). One was accepted without question, and the other caused regular fistfights (my Dad got into one while in the backseat of his old Datsun). This is not to say that we are doomed to a decade-plus of inflation – it is just that our cultural and political discourse is more akin to the 1970s, and as such, staying the course is harder, particularly when there is the potential for a wage/price spiral.

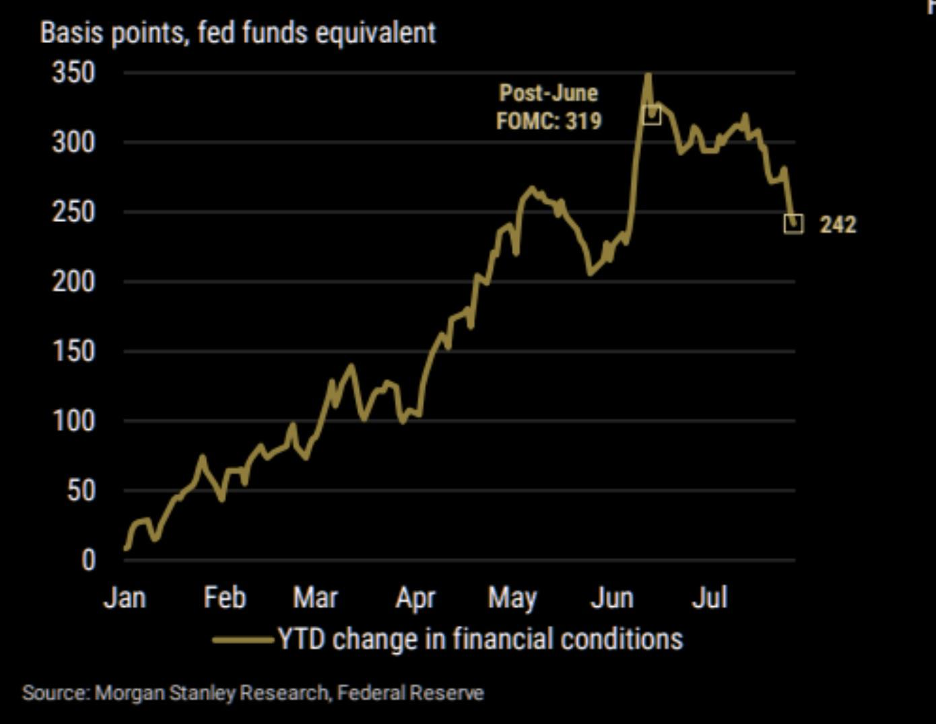

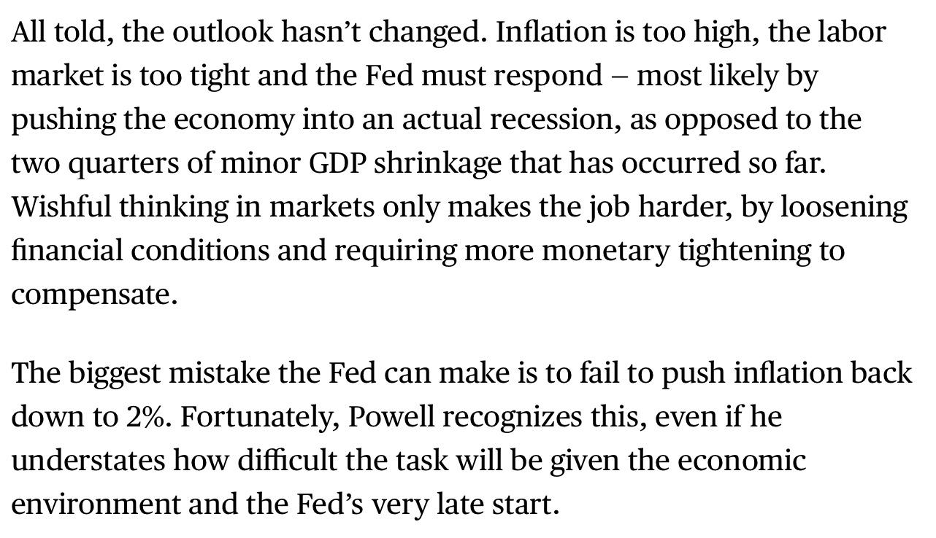

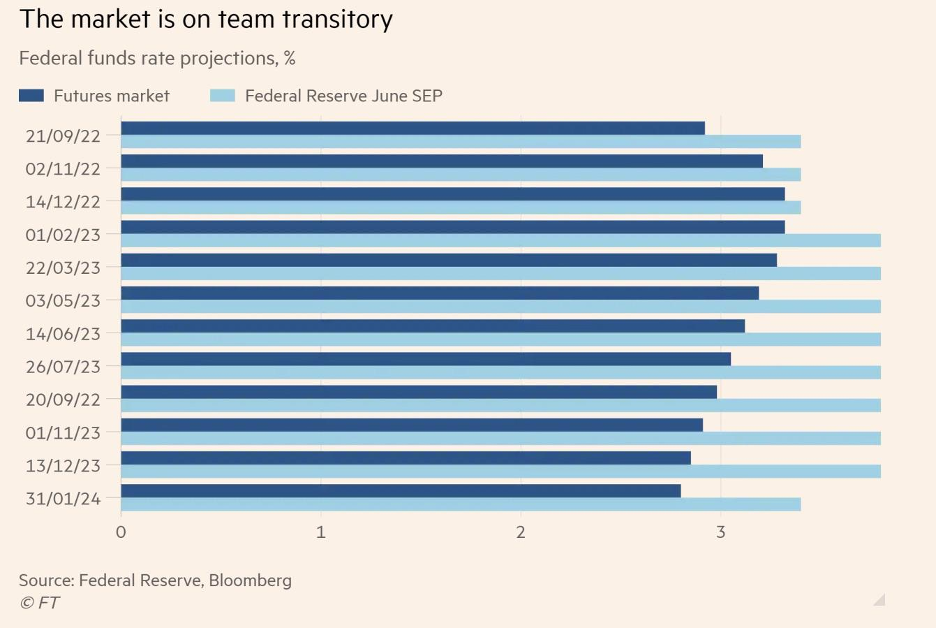

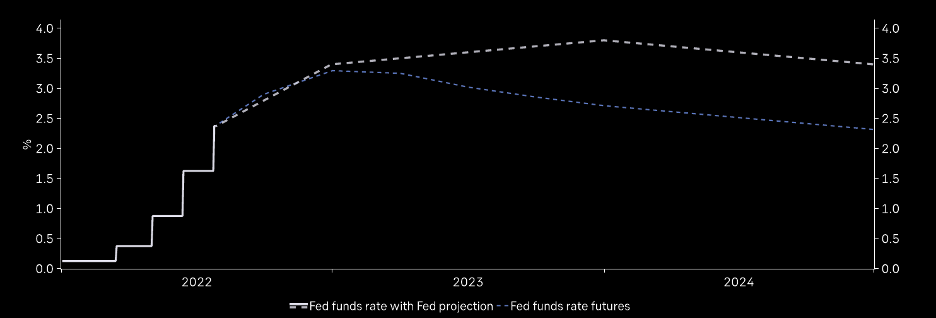

So, if Zingales is right, we still need to see a Fed and Administration willing to do what it takes, as Bill Dudley argues below. Neel Kashkari, one of the more dovish members of the Fed historically, was the centerpiece of an NYTimes article post FOMC where he was quoted as saying, “the Fed is a long way from backing off the inflation fight.” Markets typically respond to hawkish statements from dovish members as relevant. The problem with these comments is that Powell’s Fed has previously sounded hawkish and has pivoted. The proof is not getting to a neutral stance; it is taking it above and beyond what the market anticipates, no matter the consequence. Vince Reinhardt, an ex-Fed governor, remarked to Bloomberg plainly that the “Fed needs to tighten financial conditions considerably,” given inflation has permeated so much more of the economy. Financial conditions have been easing!

The referenced article from Bill Dudley points out that wishful thinking won’t help the Fed beat inflation and may require more tightening than anticipated. The driving point is this:

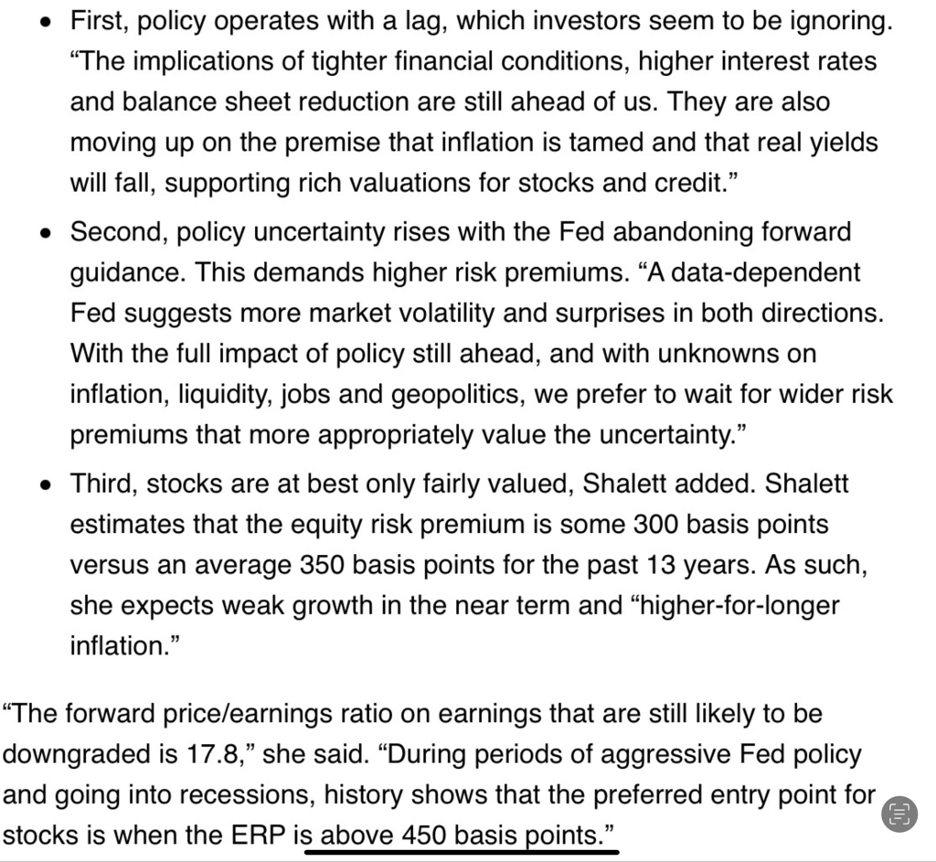

Before I move on, I wanted to add a piece from John Cochrane’s blog, an economist who has spent decades thinking about inflation in the real and theoretical world. He – like many economists, including Larry Summers – has implied that rates must go a lot higher and even Powell suggested real rates should be positive along the curve. But, and not to add confusion, a lot is going on, particularly if we factor in the experience of inflation while at the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB). It could be that Powell is playing his cards exceedingly well, that the 1970s won’t be repeated, and that monetary growth contraction will lead to a historical drop in inflation. That recession will not be too severe. We can just go about our merry way buying risky assets. Either way, please read Cochrane’s blog. Not everybody wants to think deeply about this; I get it. But, there is a reason why Powell says he is uncertain about how things will play out and why Fed governors past and present are taking the stances they are; maybe that blog will help you think about how the market, despite current uncertainty (and equity risk premium below levels often see during market bottoms) might be getting a bit ahead of itself.

And as for the market, pricing appears to have the stance and is expecting an economic slowdown, a soft landing/very shallow recession, inflation moving lower because commodities are moving lower, and a Fed that is almost done and will be cutting in 2023.

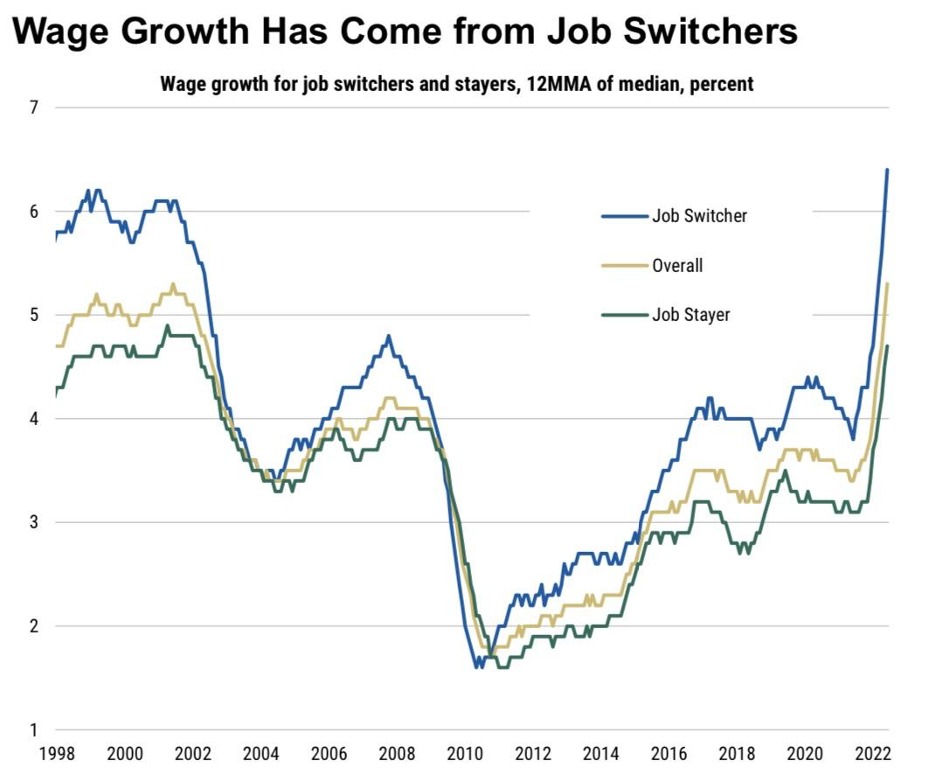

The market is reasonably good at efficiently pricing all available information and incorporating all known economic information/forecasts and appropriate policy response functions. But, the market is not that good at predicting tail risk events. One tail risk event would be inflation that stays stubbornly high and/or a Fed that is more concerned with not compounding the “stop-go” 1970s or more recent “transitory” mistake and takes rates higher than anticipated and/or keeps rates higher for longer. Let’s look at ECI and core PCE data. It seems reasonably obvious that there are some second-order impacts and stickiness, even if the market looks through the current episode benignly.

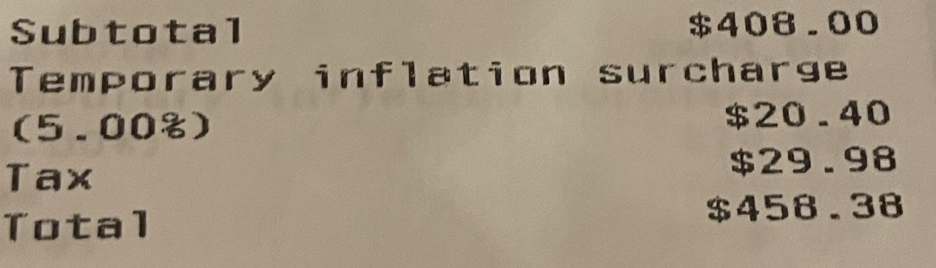

Just as a side anecdote, here is a recent tab I incurred at a restaurant (with two other couples):

For starters, the prices on the menu have all gone up ~10% YoY. Adding 5% is because they can; this type happens when inflation psychology has shifted.

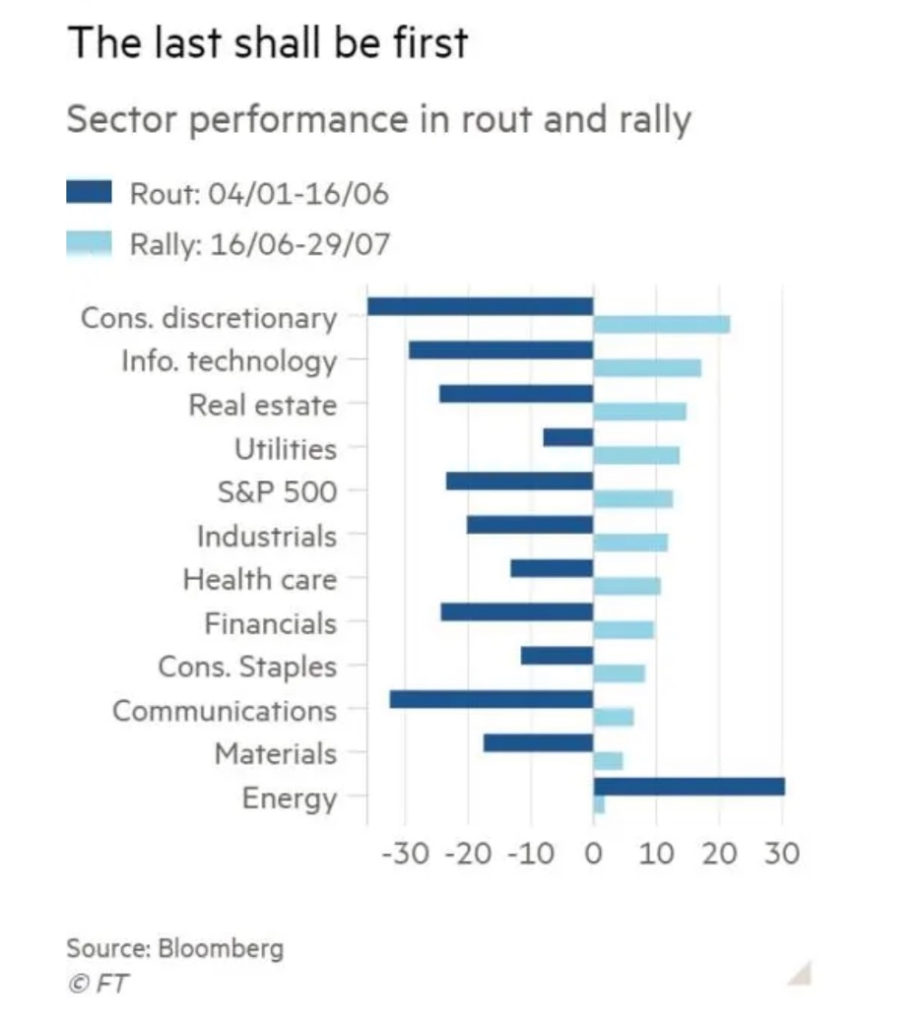

The recent market moves have been impressive and have staged quite a rally. It is not that difficult to see why. 10-year rates in the US have fallen from 3.5% to 2.6%, and compressed multiples have partially re-expanded (see chart below). This chart shows the battered names (and FI proxies) performed.

If I have learned anything over the past 20+ years, it is that the long end of the US market does not operate with textbook precision, and as I have written a lot about this last year, USTs are a global portfolio ballast. In other words, getting paid for assuming inflation risks may not be what the typical investor thinks about. They see the Fed as more serious; they assume inflation will eventually come under control, and the US will not want to risk $ hegemony. Or, it could be that the long end of the market senses a material economic slowdown on the horizon, and the market has come to expect it without extensive support. Given money supply growth, including QT, fiscal and credit impulse (see money center banks talking about getting their RWA portfolio right sized given capital considerations), that is unlikely to be earnings or equity friendly.

Things that caught my attention this past week:

Flow and Positioning:

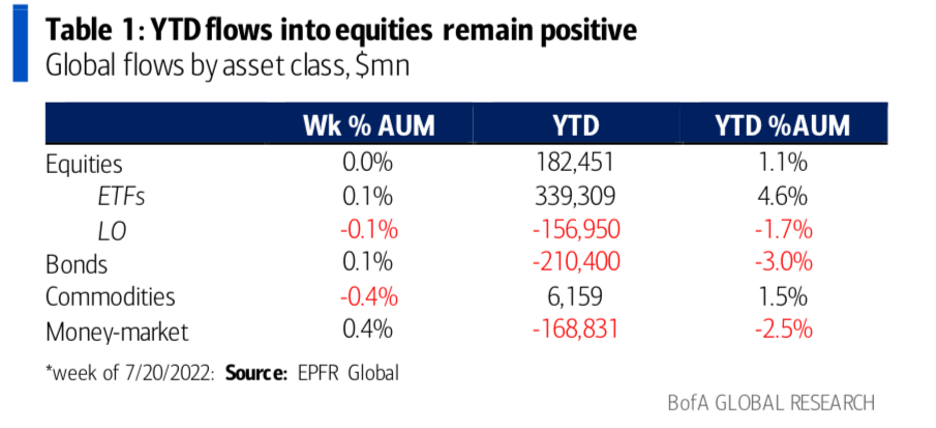

Although I regularly show ML’s table on EPFR flows and have again, it is but a segment/sample within the broader market. No definitive source encompasses all agents (hedge funds, corporations, real money, sovereign wealth funds, central banks, HNW, retail, etc.) moving money in and out of financial assets. I like EPFR because it tends to be less “hot money” and more indicative of fundamental portfolio shifts, but it is by no means a complete picture. And as the wheels of the economic machine are always turning and nominal GDP is positive, we need to appreciate that companies, governments, and individuals are engaged in earning, spending, borrowing, investing, etc, even if inflation is impacting the real value of those activities.

I have remarked that we have not seen full capitulation given my estimates that equity inflows since the pandemic were abnormally large relative to the recent past, and in fact, we may not see it. The system is ultimately a closed one. Agents produce and get rewarded, CB’s add or subtract liquidity, and investors (professional or not, short or long term) make choices about where to place their chips based upon their degree of comfort in getting an adequate return for the risks they are assuming. Although CNBC and other outlets act as if markets are all one big group of hot money speculators with impeccable timing/trading skills and no care about tax consequences, the reality is the vast bulk of money invested does not churn all that much. If there is nominal growth – and there is – money is coming into the market.

While I don’t agree with Tom Lee’s calls about this being like 1982 and the beginning of a new bull market, I do respect that the market is not going lower. Whether it should race higher is another story.

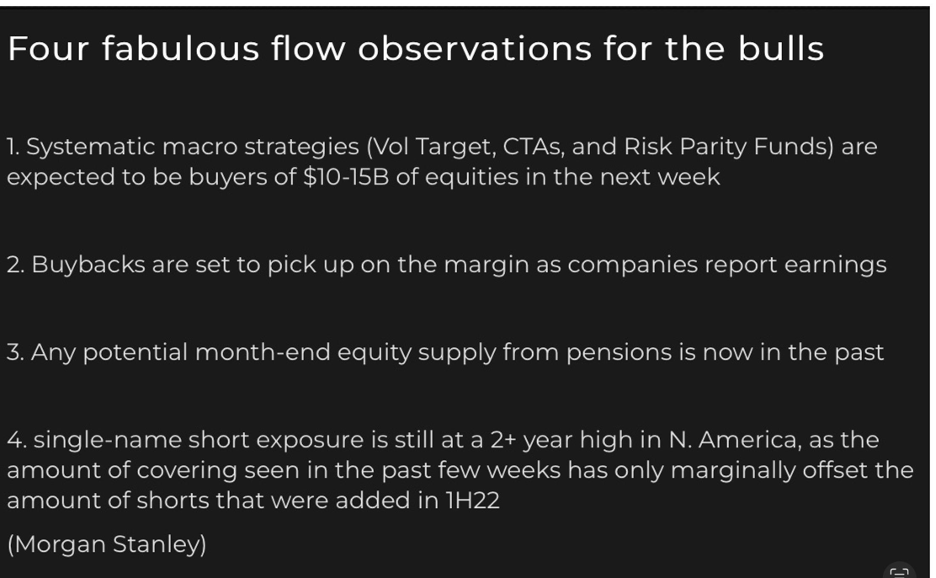

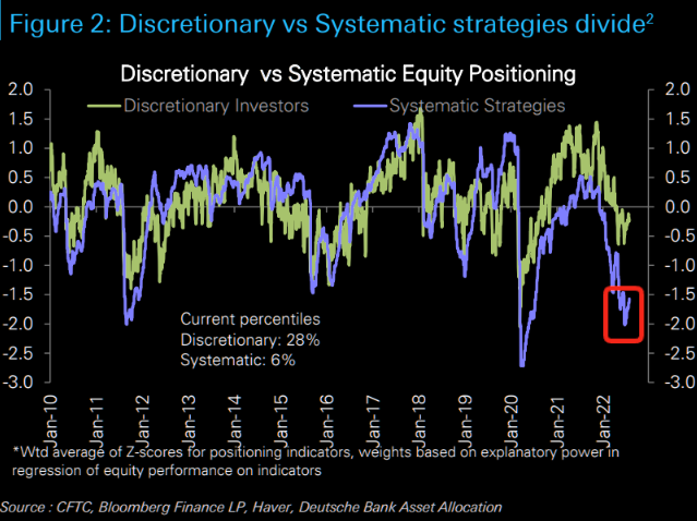

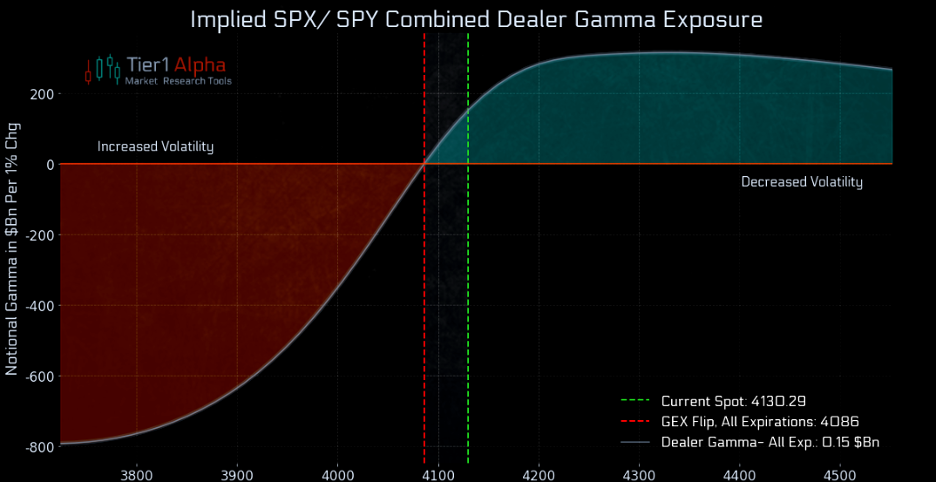

But, long story short, I think what is going on and has been going on is that the speculative side of the market is acting on “less bad than feared” or “Fed pivot” (softish landing), and with it, some good trading gains. A good snippet from MS and DB suggests some hotter money flows are offside. Against that is that we are running up now to long gamma clustering.

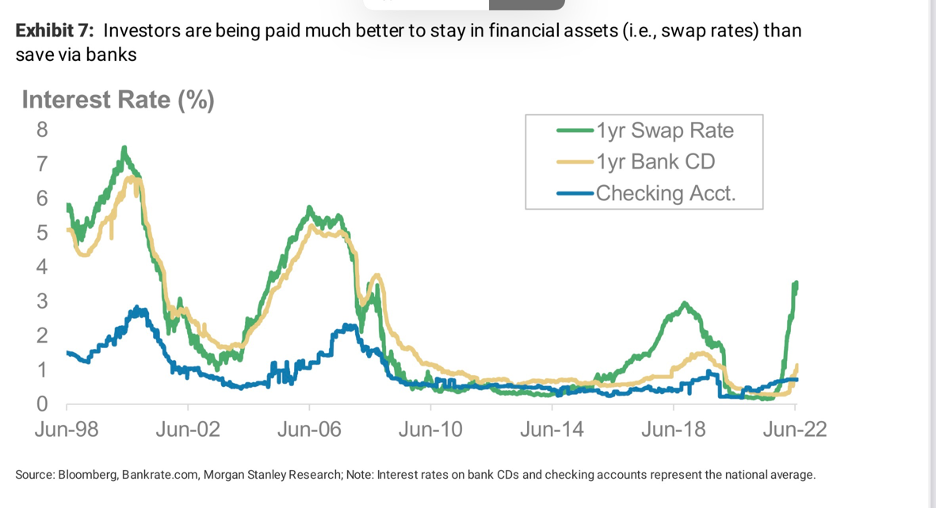

To add some context to that, I had a call with my money managers, and they noted I had some more excess cash than normal. I asked them what rate was paid, and keeping markets parked at a bank was painfully low.

The net of all of this is that we are smack in the middle of a whole lot of noise and uncertainty (add in Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan for good measure) that, at least for now, appears to have markets short covering and perhaps pulling in some cash from the sidelines (hearing TINA again).

Has the bottom been put in place? Is the bear market over?

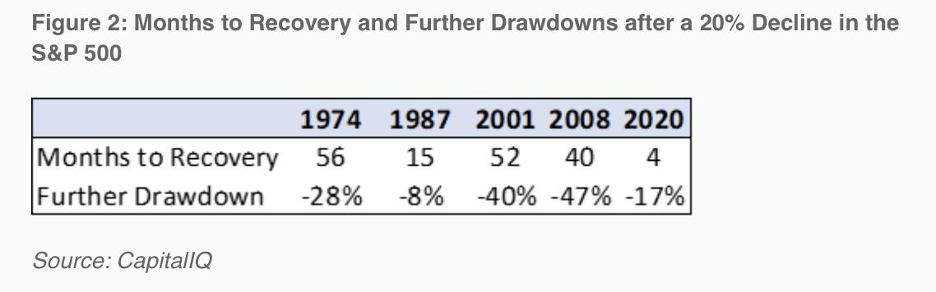

Honestly, I don’t know, but I am still inclined to think it is not. For starters, bear markets typically last far longer than this current episode, and the liquidity picture is not positive at the margin and certainly not the picture we saw in 2020. Here is a table from Dan Rasmussen at Veritas that would argue we are unlikely out of the woods.

Morgan Stanley’s Lisa Shalett (along with ML, who is still very cautious about putting new money to work, as I wrote last time) is still cautious.

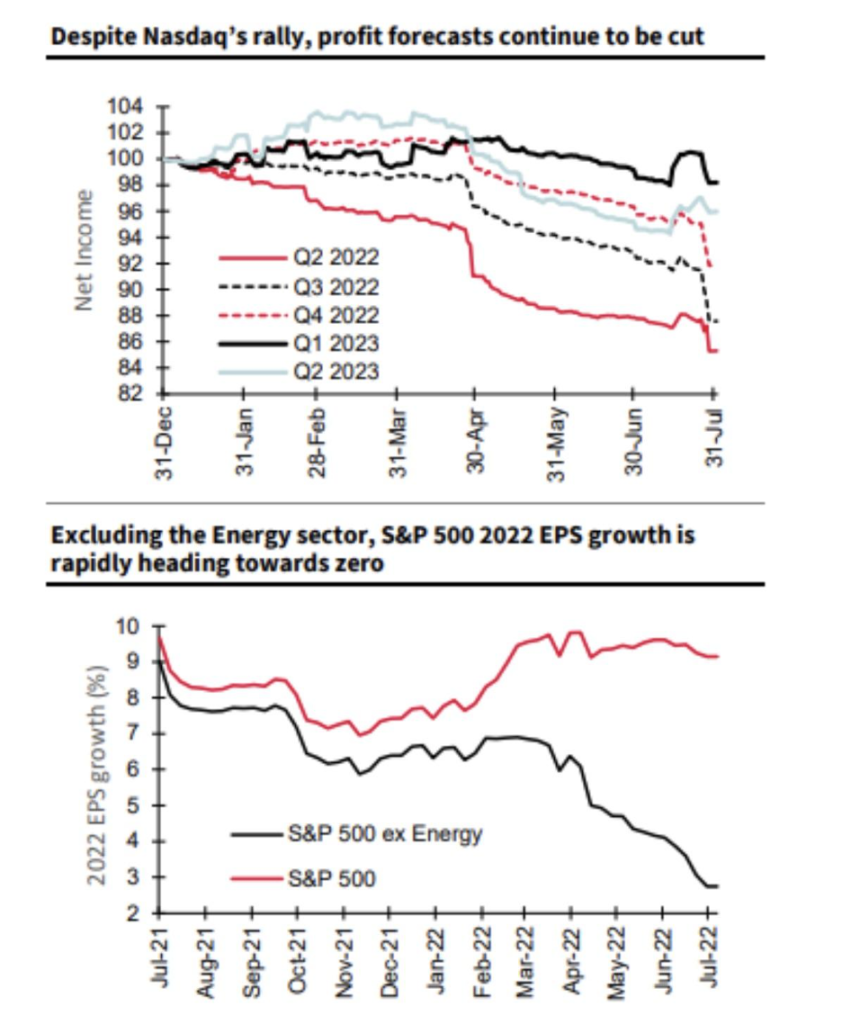

As for earnings, they have come in decently overall (less bad than feared), but the guidance has generally been cautious and trending in the wrong direction.

Mike Hartnett at ML has some points worth highlighting, suggesting the market may be getting ahead of itself.

Other Tidbits:

Musk-Twitter

I have written a fair bit above, so I don’t want to head too far into the TLDR space as it is the summer, but I did a fair bit of reading on the subject matter. As I wrote last time, there was a hearing regarding whether to expedite the trial in Delaware. If it were expedited, it would be favorable for Twitter. I suppose it has been marginally, as the stock has reached above $40. Tesla has been another matter, as speculative call buying has been quite extensive. But, there is still this matter, and with it, whether Musk will be forced into buying Twitter or, in legal terms, honoring the specific performance clause he willfully signed.

The most relevant case is Decopac, in which Kohlberg (of KKR fame) sought to have the deal terminated on material adverse effect grounds. It was not terminated, and Kohlberg (despite financing issues) was forced to comply and perform.

It is hard to figure out how Musk gets out of this. Financing is in place, and even if it were not, as per Decopac, he could still be on the hook, given that he has sought to blow the deal up and can afford to buy it anyway. It is all just a matter of how much stock he will need to sell at the margin.

Maybe some of the stock rallies relate to the Manchin Schumer bill, but it would be hard given his buying cohort and the price points for the subsidy to be of material value. I have maintained that shorting this stock is hard – heck, shorting generally is hard. For starters, the winds of EV are a tailwind for growth. Whether they can continue to grow at the 50% per annum speed the company forecasts is still a question for me, given a. Economic slowdown globally, b. Competition heating; c. Supply constraints and factor costs; d. Geopolitical issues with China, which have been a margin positive; e. The need to continue to build more plants to support growth; f. Ongoing legal issues and other distractions.

I am slightly short and added some yesterday above $900/share, but I am trading it around and always super cautious.

Deglobalization and the German Lesson:

I found this article in Bloomberg – particularly the bits from Ken Moelis – very insightful.

It generally does pay to be very optimistic about the future, and the US in particular, given we have physical resources to sustain ourselves. Still, the splintering of the world – something I have remarked about – is not something to be taken lightly. It brings additional costs/constraints and pressures into the equation while reducing visibility. Risk premiums may still be too low given the expected operating paradigm.