It is amazing how everything changes as you get older. These past few weeks, I was in Austin, Texas, visiting my son and went to the Texas-Alabama game, and in Carmel, attending the daughter of a friend’s wedding. We went out a few times in Austin, and after the end of the trip, I needed a “minute…er, few days” to feel normal. Then, my wife and I turned around, flew out to SF, and drove to Carmel for a destination wedding. Happy to be there, but after a few days of events, I was exhausted. I used to love to travel, go to sporting events, be out in bars, and the like, but I just don’t do that great with those things these days. I can only handle a few drinks when I am out (I overdid it the first night in Austin), and I am pretty careful about not drinking at all during the week.

One good thing about long trips is that I get to read and think about all sorts of things, mainly markets, and the economy. I have written this before, but one of the edges you develop working in a macro hedge fund is that everything is not only geared towards taking and managing risks, but looking around corners and trying to order the many issues and concerns that are known, and constantly assess whether there are things you don’t know or cannot imagine. So, you are always prepared, knowing how marginal information and data affect the economy, market, and investor psychology. This makes taking and managing risks a bit easier.

When the pandemic hit, I was aware that the hedge fund I worked for had contingency plans for such an event, and we had studied many previous pandemics. So, I knew this was something important. I remember talking to a friend who gave the standard line at the time, “it is like the seasonal flu.” I simply listened. Sure, it could be benign, but what if it wasn’t? I figured slapping on some risk asset shorts was worth it.

I have recently remarked ad-nauseum about inflation and the Fed’s new monetary regime. A part of my concern about the regime was that it lacked clarity and was asymmetrical, meaning that upside inflation surprises above the target would not be offset by pushing inflation below the target. That felt to me to be an inflationary drift. I understand where the Fed is coming from and the concerns it has for operating near the zero lower bound (ZLB), but between the excessive stimulus on both the monetary and fiscal side, supply side factors stemming from Covid, and the Ukrainian war, such a policy was simply an idea implemented for an entirely different paradigm. Things change.

People ask me all the time why I studied economics in college. The answer is that I didn’t have to read very much for those classes, which was important because I was playing sports, in a fraternity, and having a grand old time. Plus, once you figure out supply and demand and some other things like the time value of money, each additional class is marginally easier. But, nothing could be more boring than studying economics. I can still see my professor drawing all sorts of graphs developing the ISLM model, and I am somewhat clueless about what he was talking about. Knowing now what I know, I would have studied history or economic history (although I don’t believe it was offered as a concentration) and been more focused on my studies. That’s probably one of the reasons I read so much now. Partially because it interests me and partly because it fills a gap in my knowledge of how economies have evolved throughout time and why things are the way they are, which is helpful to contextualize current events and take and manage risks. In 2008, one portfolio manager I worked with named Marc Cheval impressed me greatly because he seemed to have gamed the sequences of a solvency crisis. He was rarely surprised and was a student of economic and market history. Obviously, he killed it.

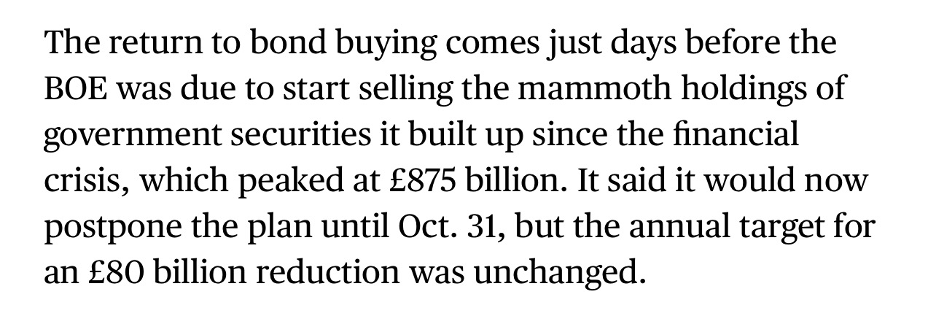

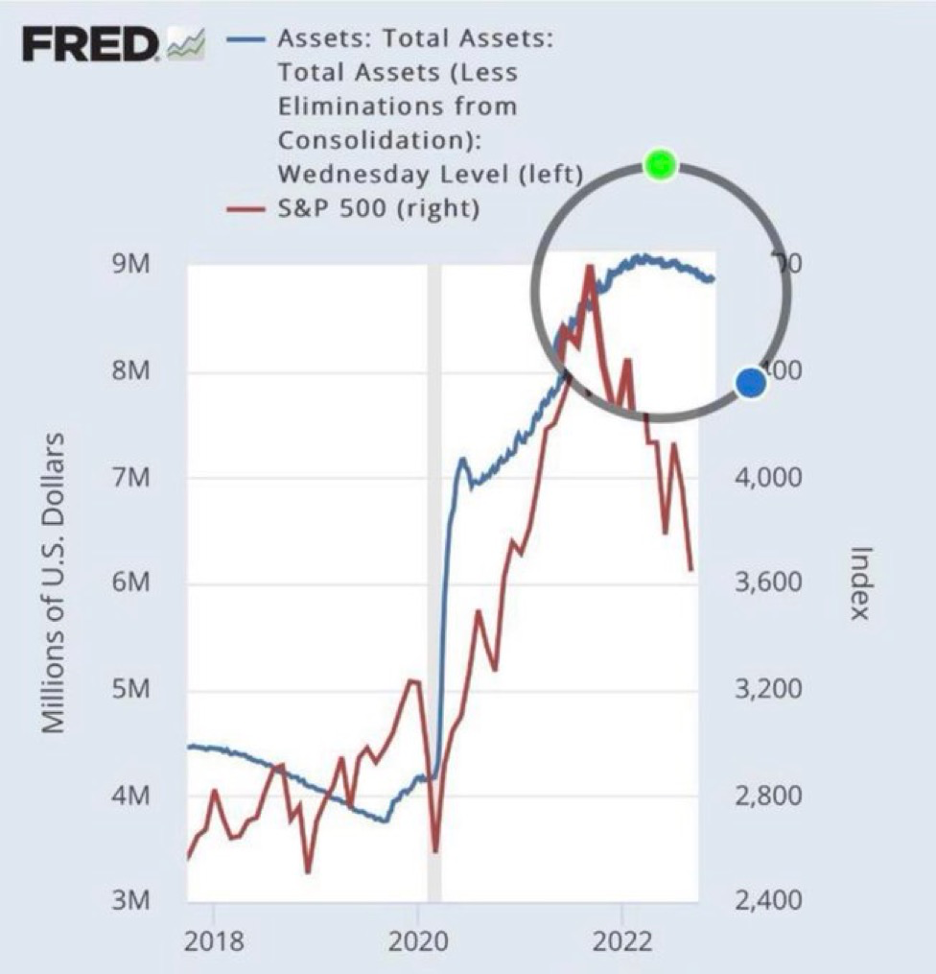

I mentioned recently that I had read Bernanke’s latest book and was finishing Edward Chancellor’s “The Price of Time.” Bernanke’s book makes a case for why central bank policy and the Fed, in particular post GFC has evolved how it has – which gave rise to the average inflation targeting regime the Fed adopted (and they have plans in the lab for even more adventurism). If the Taper Tantrum and recent Bank of Englands action to step in to do QE to address disorderly/volatile Gilt markets just days before commencing QT suggests anything, it is that once activist and creeping monetary policy are set in motion – to operate through the portfolio channel – it is exceptionally hard to reverse. That is because the system becomes addicted to the medicine, adds leverage in new and clever ways, and the withdrawals can be highly disruptive. This clip from a Bloomberg article is perhaps evidence that the UK is a bit dope sick, and the BOE needs to manage the situation more actively. That being said, the underlying problem – inflation – remains.

This point that the pain of withdrawing excessive liquidity can be material is essentially what Chancellor’s book addresses. However, he also covers historical periods where just plain easy money/low rates without QE assistance were the drivers. His general premise is Minsky-like: “stability breeds instability,” Low rates cause excesses to build up that is painful to reverse. He lays out the case very thoroughly (and at times redundantly), exploring the historic premise for interest rates, which were frowned upon as usurious for a long time, even at low levels. His basic point is that an interest rate accurately rewards savers and investors for taking risks. He uses the idea of “Price of Time” to point out that artificially manipulating rates from that which is needed for commercial reasons serves to ultimately distort the real economy from its primary purpose because it forces savers and investors into taking more risk and improperly valuing time, or the trade-off between current and future consumption. If the nexus of the BOE action were related to LDI margin requirements, Chancellor would probably argue that LDI product growth was due largely to excessively low rates relative to liability streams (themselves set perhaps casually), and the need to find excess returns (which tend to create bubbles). In any event, Chancellor can come across as a bit purist or Austrian School, but that school does have some virtues. As has been remarked, “Capitalism without a default is like Catholicism without hell,” we are simply living in a period of policy imbalance that is not allowed to clear, and risks are underwritten at too low a premium. Eventually, the chickens come home to roost, perhaps a political mistake is made (such as the Truss policies), and the system is thrown into disarray. Chancellor deftly catalogs through history that these lessons have been clear and that monetary (and fiscal largesse) have real consequences. And when you have a mess, solve the core issues versus kicking the can down the road.

I found both books to be well worth reading because they are contrasts in approach that are at the heart of economics and markets. We know – and I will show some of this from a good piece from NYU Professor Aswath Damadoran – that economic uncertainty and volatility tend to go hand in hand with asset market underperformance. Since 2008, officials have been trying to reflate a system and had some tailwinds to doing so, inequality notwithstanding. Inflation changed all of that. When you are in that state like the UK is, providing energy price caps and talking of extending tax cuts funded with debt, your currency and debt markets can run into turmoil. That is a plain and simple emerging market territory, as is the IMF imploring you to pare back such policies (which, oddly, a day after BOE intervention was met with Truss in intransigence.

That said, the UK is not alone. The Eurozone and Japan (currency intervention while still doing YCC) are also in conflict policy-wise. However, what makes the UK worse is the current account deficit (similar to the US) and a balance sheet size relative to the economy that is twice what it was during WWII! I have mentioned that the US was getting dangerously close to fiscal dominance – whereby the central bank fails to act because of interest costs causing budgetary issues – but for the here and now, Powell is sticking to the script and is seemingly willing to break some eggs.

Not sure that what the BOE has done foreshadows a Fed pause, pivot, or additional QE, but that possibility has to be on the radar – and I don’t think it is long-term risk positive. How allowing inflation to stay structurally higher and for longer helps matters, I don’t know (one could argue the opposite, using late 1970’s early 1980s Volcker as an example). I would suspect the Fed to get rates an additional 100-125 points by the end of 2022 as articulated and to wait and see how inflation behaves while QT operates in the background. Either way, it is likely to be very turbulent going into Q4, as earnings are released, and there is potential for further FedEx-type announcements.

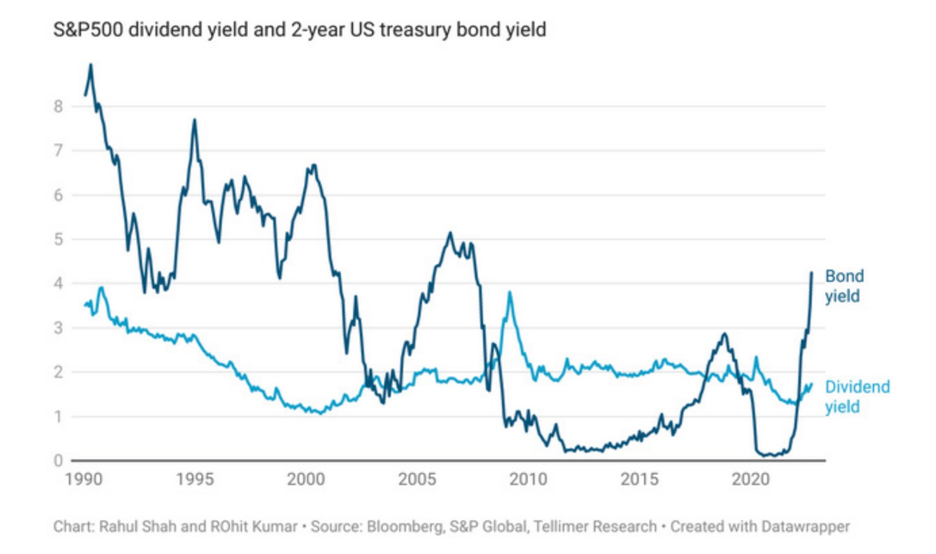

Currently, markets are giving back a portion of the gains seen in the past few years, which will probably worsen. My base case is probably 5-10%, but it is certainly plausible we get a bigger flush below 3000 for any number of reasons, and I am staying extremely defensive. With cash and treasury yields higher (and well above dividend yields), there are alternatives to owning equities.

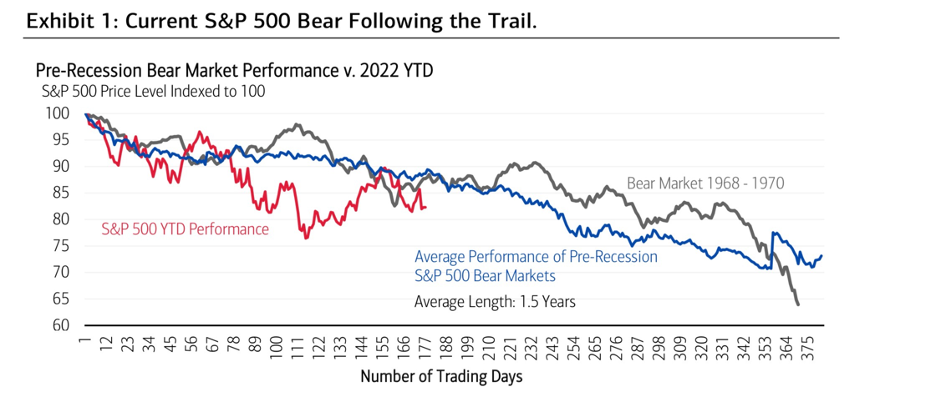

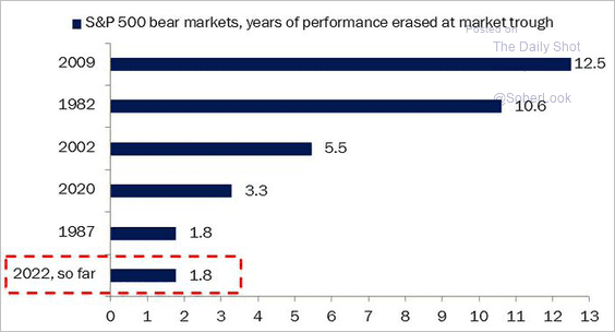

We are rarely in bear markets, but they do happen. Here are some charts that put it in a bit of context. So far, pretty mild.

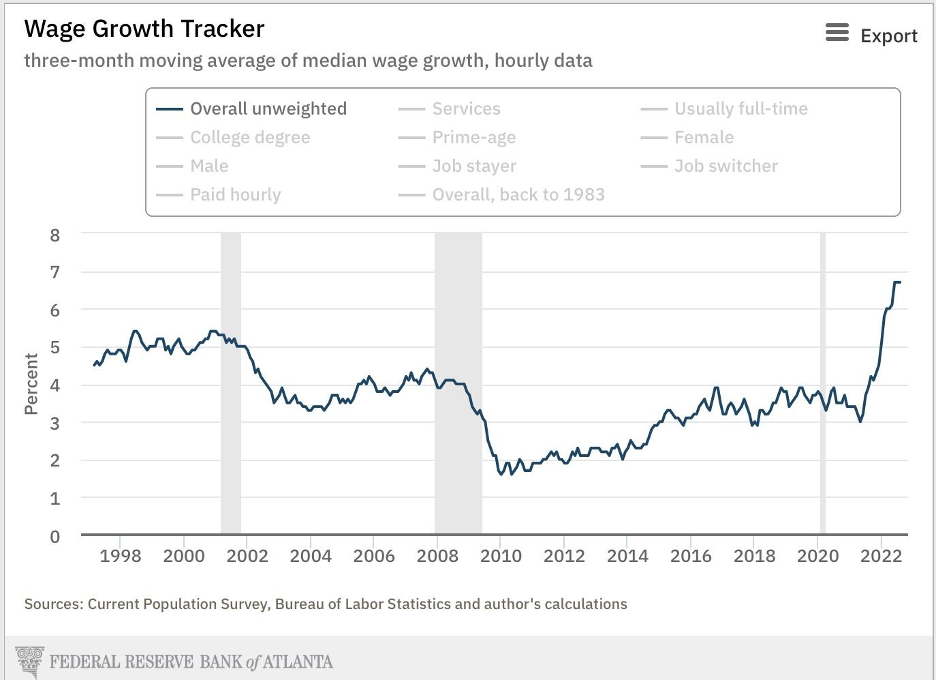

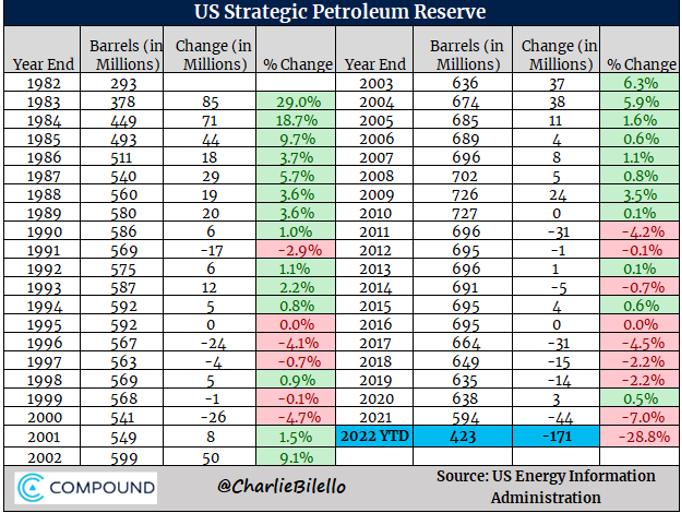

Market talking heads are suggesting the Fed has gone too far, too fast. You listen to David Kelly at JPMorgan or Jeremy Siegel at Wharton, and they seem to be barking at the moon as if this will merely solve itself because gas prices have come down (see SPR draw below, huge!). Yes, monetary policy acts with a lag, and they may have gone too far at the expected terminal rate. Still, inflation – particularly shelter and wage inflation – is running too hot (see below). As Jason Furman suggests

Looking at some items (gas or lumber, for example) misses the point of the drivers of sticky inflation. Officials let inflation out of the bottle, which will most likely induce a recession to bring things back in line. Here is a good Bloomberg opinion piece suggesting a moral case for what Powell is doing, and the noise (from people like Warren) misses the mark.

But, putting all that aside, Jim Chanos said something very wise recently: if US real growth potential is 2%, and the inflation target is 2%, then why in the world can we not live with 4% 10year treasury rates? That structural problem resulted from a year of easy money and excessive monetary and fiscal support. Working through that will be painful, and letting the air out of the balloon will take time.

I would caution against those who believe the markets will win the day and officials will back off. There may be more moments of smoothing markets – as the BOE and BOJ have done (which may spook weak-handed speculators or excite the buy the dip crowd). Still, those are designed to prevent severe dislocation (UK rates volatility is insane), calamity, and contagion (or some political discomfort), not reverse course as inflation still lingers too high above targets. Trade, as you see fit as markets, do move, and even delve into some assets at depressed levels (been buying more energy names on pullbacks – see SDR release history below, which has impacted energy prices). But, fighting the Fed on the way up was a mistake, and so is fighting the Fed on the way down. There will be a good time to dip a toe and/or go all in, but we are not there yet. Markets usually bottom after a recession hits, and the consumer (70% of the economy) is still employed and spending (although veering dangerously on the credit side into record territory, ex wealthy. In the meantime, cash is king.

Other things that caught my attention:

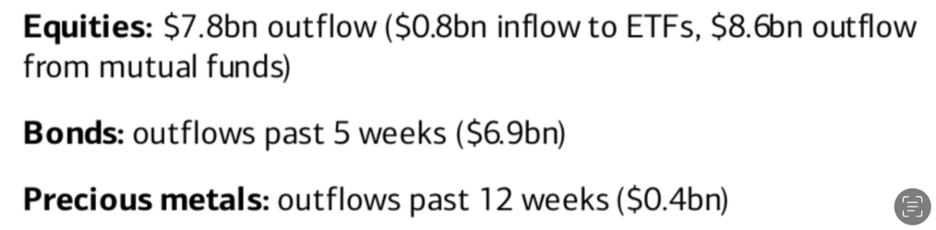

Positioning & Flows:

As you would expect, flows out of risky assets continue.

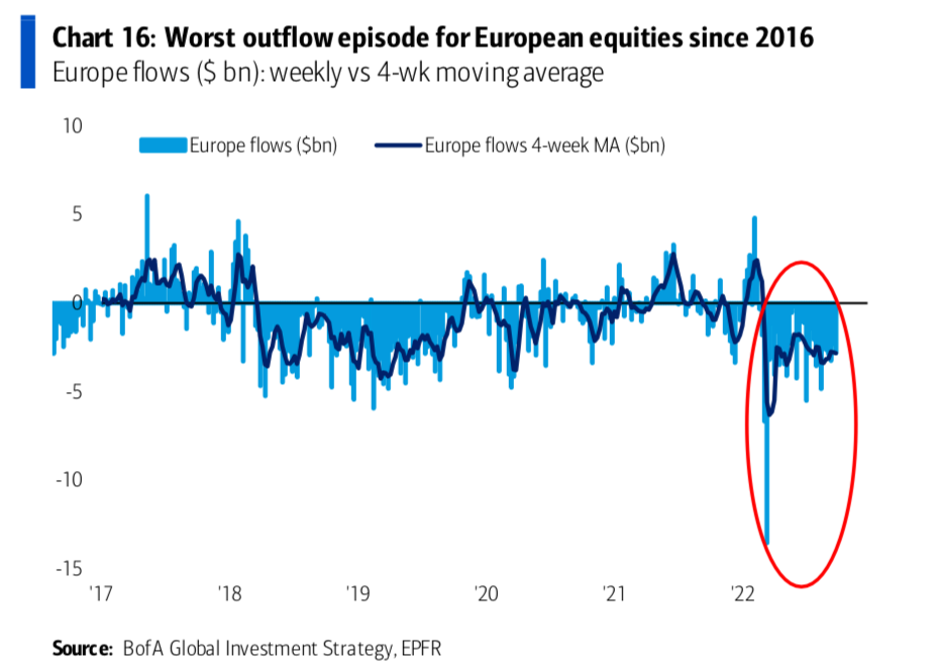

And Europe is continuing to leak, for obvious reasons.

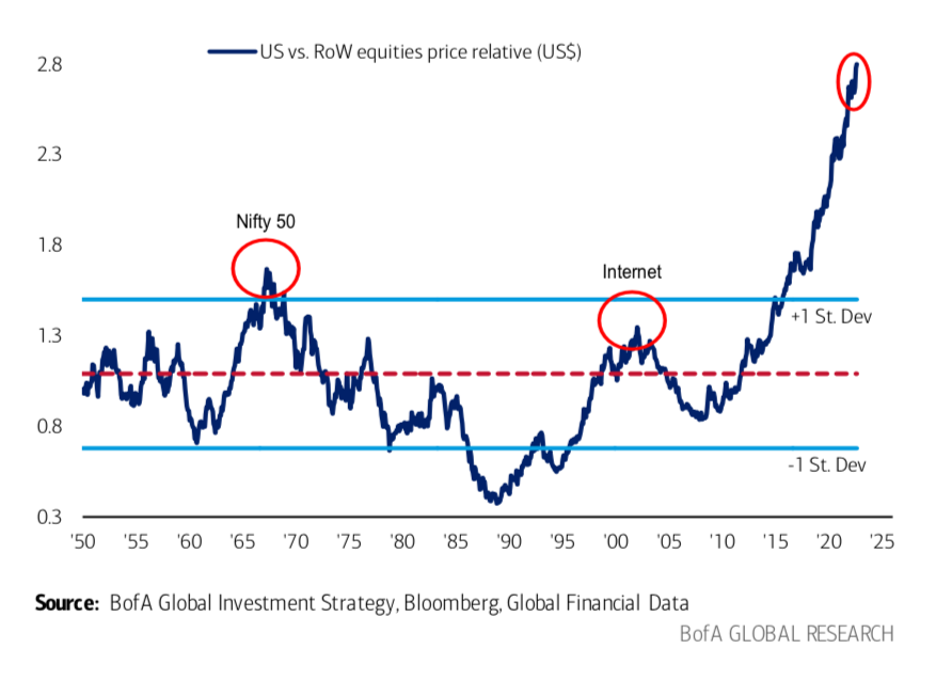

Interestingly, the US is still well above normal positioning relative to the rest of the world, and the dollar strength is helping to cushion asset performance. But, it is still very extended, particularly when many of the largest holdings are in firms with global exposures, and thus likely continued negative impacts on earnings, not to mention going forward demand. I have seen reports – and it shows up in some of the tic data – that Europeans are beginning the process of selling some assets. Keep that in mind if things get worse there because when investors have to sell assets under duress, they are likely to sell these assets.

There are mixed reports on the hotter money front, so it is hard to know exactly what to think. It is one reason I keep an eye on the shorter-term speculative activity but focuses more on the changes to slower-moving flows. Either way, it is just plain hard to know the extent of the exposed positions, trigger points, and why I rely on technicals (Tommy in particular) to stay on sides. One lingering issue is sentiment, which is distinctly negative, but as Tommy has pointed out and I have experienced as well, it can stay that way. Crashes can occur despite that, often tripped up by a liquidity event. Every time during 2008 it looked safe to go back in, another shoe would drop. That’s the nature of a system de-leveraging amidst uncertainty and perhaps policy errors.

JPMorgan

JPM’s head of US market intelligence, Andrew Tyler, with stats on how much selling has taken place recently:

1. HF net selling picked up this past week with net flows in N. Am. at a -1.2z level by Thurs (so could be lower with Friday’s data). Not there yet for this metric, but getting closer…

2. HF shorting has been increasing, with ETF shorts rising quickly. The 20d z-score for ETF shorts is close to a -2z level

3. Retail selling has picked up since late last week with 5d flows near levels at which markets often bounced

4. US ETF flows (not HF specific) are fairly negative on a 20d basis as well

5. CTA positioning is near May / June lows

Our Tactical Positioning Monitor, which tries to aggregate much of this, is down at -1.3z on a 1wk basis. We are not there yet for this metric either, but getting closer.

GS

As of Friday global long/short ratio is at the lowest level since June 2019 (180% or the 9%-ile vs the past 5 years), and Long only community has been running the highest levels of cash for five years. Feedback from desks is that the HF community is scared to lean into shorts despite feeling the trajectory is lower. The Long only community are shocked into inactivity…. running long cash (worried about redemptions), de-grossing in growth, but otherwise sitting on hands for now. Asset allocation and the need for portfolio rotation out of equities and into cash/bonds to match asset vs liabilities a topic last week, as was retail behavior and when we may see household equity ownership start to reverse from recent all-time high levels.

Although I have done OK with it trading in and out, one trade that has surprised me is that the VIX has not moved into a distressed zone that we have seen in the past and is certainly not on par with what we are witnessing with rates and fx spaces.

Morgan Stanley noted that perhaps the VIX isn’t being bought because stock ownership and risk levels have been pared back.

1-year VIX “beta-to-SPX” down to 1.2x – the lowest level in 1.5 years

MS’ QDS team’s view is that light positioning likely continues to contribute to the minimal reaction in VIX since July. In other words, investors don’t need to hedge what they don’t own. And this has brought the one-year VIX beta-to-SPX down to 1.2x, or the lowest level since March 2021 (just the 1st and 13th percentile vs. a five and ten-year look back, respectively).

I would prefer to see some equity market capitulation for a tradeable bottom. That has been true of many segments that were overbought post-CoVid – like unprofitable tech. Nevertheless, despite the market retesting the June low and VIX picking up a bit, it has failed to go vertical. I am still positioning for that. I also would like to see BTC crack below $19K, although I can appreciate that there may be some medium-term allure to this holding some value given the current climate.

Where is fair value for stocks?

This is a loaded question. For starters, indices are made up of stocks of different companies with different growth opportunities, managerial competence, maturity stages, competition, demand elasticities, operating leverage, etc. We know that many of the red stocks will be higher in a few years. But, we also know that entry points matter.

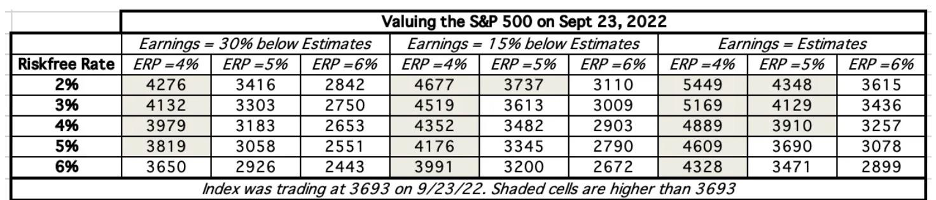

The back-of-the-envelope thing many people do is put a market multiple on forwarding earnings (often one year ahead). Which multiple, of course, matters because they are not stable. We can infer that the commodity multiple (1/WACC) is a good place to start. Since WACC is a function of risk-free rates and the cost of debt and equity, all of those have gone up, the multiple has gone down. That’s broadly been the bulk of this year’s downward stock adjustment. In any event, one can generate a table of things like different multiples for different EPS scenarios to see whether the current market is too optimistic (see one below from NYU Prof Damadoran).

The more challenging question, however, is not whether a recession will impact EPS broadly because it will (and we have historical evidence of typical recession EPS effects), but what type of equity risk premium ought to be given that we are likely to be in a structurally more uncertain environment with more inflation volatility.

Since I am far from an equity market analyst, it would be foolish to suggest I know the answers. For now, the things driving my investment views are simple:

- inflation is a problem (and I have been on this for well over a year)

- Rates are too low

- Tightening will cause economic and market dislocations

- We are unlikely to go back into Davey Day Trader “stocks only go up” market

- Stay defensive, try to tactically exploit the market’s unwillingness to accept a new paradigm

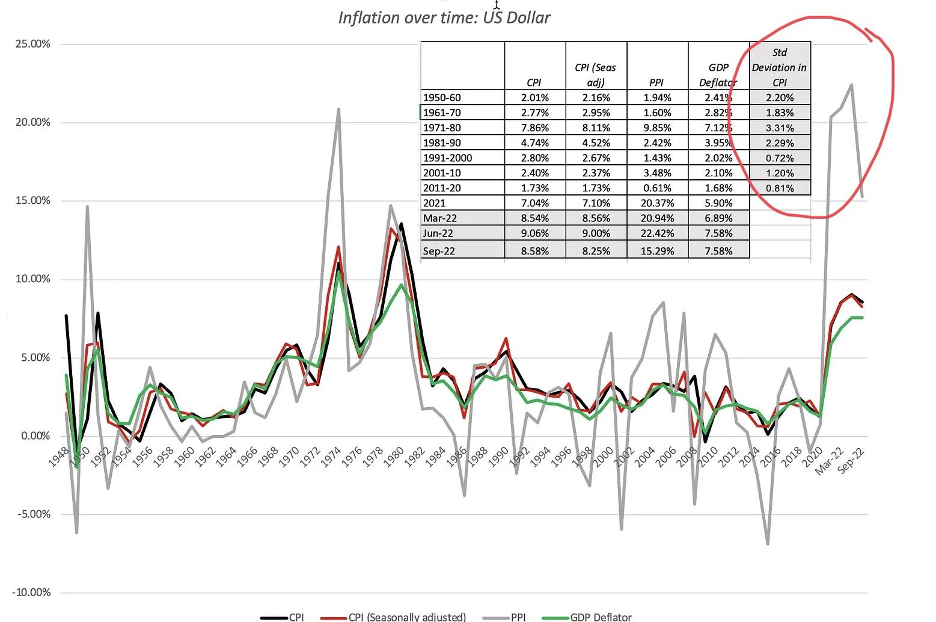

But, I came across this piece from NYU Professor Aswath Damadoran, which has an array of good nuggets here to help define where fair value might be, and how to think about the role inflation uncertainty plays in that exercise. . Here is one good chart that I wanted to highlight because it reveals that inflation volatility matters. The last decade was unique in terms of low inflation volatility AND very easy money. If we study the table within the chart further, we see that the ’20s are looking a lot less like the 10’s, which is unlikely to be positive for ERP going forward.

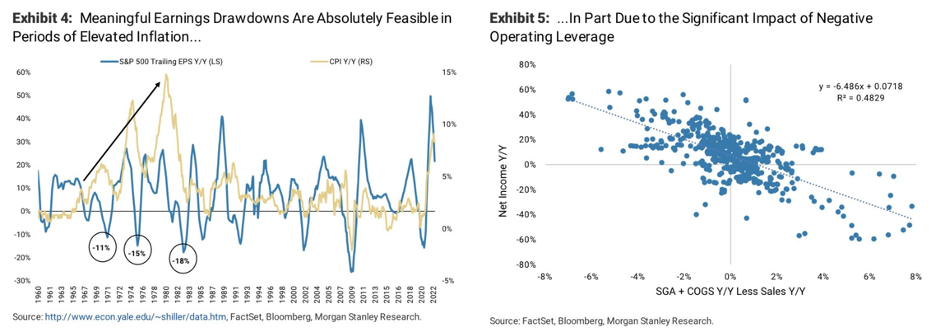

Mike Wilson had a good set of charts this week that reveals EPS drawdowns despite revenues rising (nominal GDP positive) is certainly plausible and why.

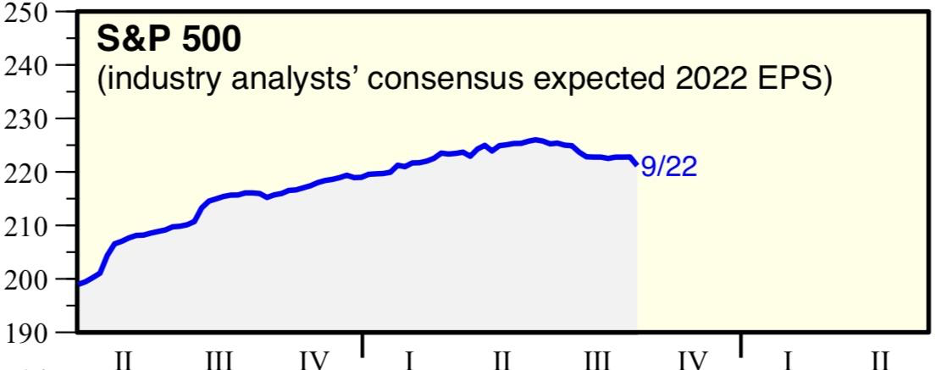

And yet, despite annualizing to about $200 EPS for the year based upon first two quarter run rates, EPS expectations for the full year still seem a bit high.

Other Tidbits:

How did we let it go so far?

I know Jonathan Haidt (as he is the brother of a good friend), and I think the world of him. I have read everything he has written. It started with a desire to understand the psychological underpinnings of political polarization. Anyway, he is a well-respected social psychologist that teaches at the NYU Stern School and a general thought leader who is published and has a wide following. A few years ago, I was at his sister’s house for a private gathering after he released “Coddling of the American Mind,” and he remarked to me how difficult it was to be in academia and that he was “extremely concerned” about the future based upon what he is seeing in the academy. His basic premise is that as this cohort (of snowflakes seeking safety/requiring coddling) moves from the academy to the wider world, our institutions will get infected with some of the worst elements of their behavior/expectations on the one hand, and just polluted thinking on the other. Fwiw, I am currently reading Rolling Stone magazine founder Jann Wenner’s autobiography and his role in the counter-culture movement, and I DO appreciate that these cultural movements are important, often needed, and should be celebrated. But, I think we can draw lines between effective and ineffective activities that uphold the basic premise of our system while trying to improve it.

He recently penned a superb article about why he left an organization he was affiliated with for many years. I think his writing in this regard is extremely thoughtful, rational, and well worth going through.

Once again, because I don’t want to make political statements here, my point is not whether society should be just and fair because it should be. The point is whether the means (policies, approaches) we seem to be “accepting” are the right ones and likely to be long-term effects. As I have written quite a bit about the ESG movement, it has the same tinge of a good idea and movement, executed and implemented in a half-baked ineffective way.

Oh Please

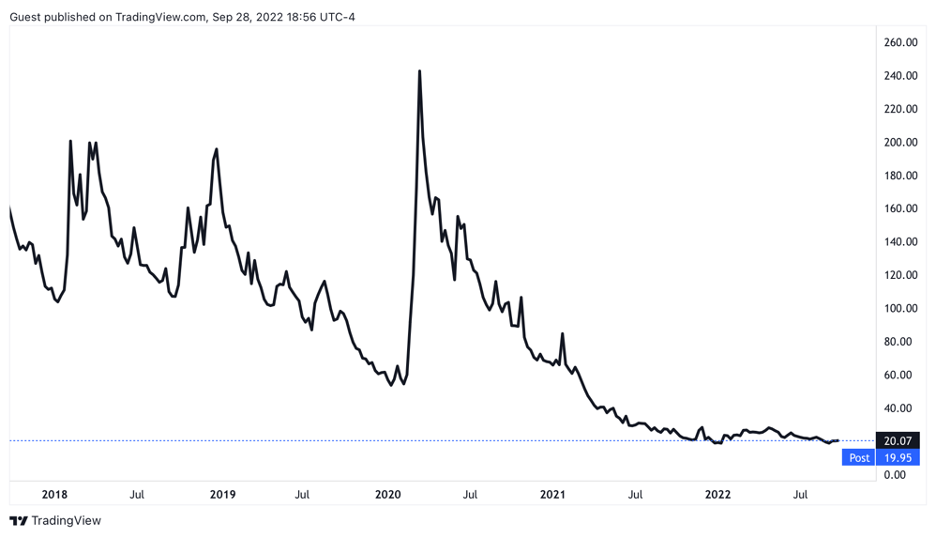

The Cathie Wood phenomenon (or why Jim Cramer is still a thing) will never make sense to me. When I was at Moore, I used to hear about all of these people who seemed to have the magic touch, only to hear them blow up a year later. Louis Bacon has his foibles but is one of the greatest investors of all time (see the track record and operating through different eras). As I have mentioned, ARK is a super long-duration equity fund with questionable risk management processes.

I was watching the Yankees game (good for Aaron Judge – I ran into him at a gym in the Bahamas a few years ago – he is freaking enormous), and there was a good debate on the quality of Ron Guidry’s Yankees strikeout record versus Gerritt Cole’s and how to contrast the eras. One way is to look at league averages and how their performances are compared. Guidry’s was 98% better than league average, and Cole’s 48%. But, league averages are likely different because the strikeout is an accepted cost of doing business in today’s baseball, as current league averages are higher.

Anyhow, I have remarked on Twitter that giving a microphone/platform to Cathie Wood at this point is patently absurd. Nice lady, happy for her success, but what her track record reminds me is much longer than her time at Ark, and it is not Hall of Fame material. It reminds me of Brady Anderson, who used to play (mostly) for the Orioles. He hit 210 HR’s over his career over 6500 at bats, or a rough 3% of the time. In 1996, he hit 50 in 579 at bats, or roughly 8.6% of the time. If we take out the 1996 results, he homered roughly 2.7% of the time he had an official at bat. So, 1996 was over 3X his non-exceptional career averages. He does not have a plaque in Cooperstown.

Now, Brady Anderson was a good baseball player, but if you are responsible for paying his salary, do you overpay for 1996? Well, it wasn’t his first season, and it is certainly plausible that as he developed, he learned the pitchers, his strengths or whatever, and was going to stay at a similar trajectory. But, more than likely, if you were not forced to act (contract not up for review), you want some more time to see what skill level there was. Over 15 years, he made about 2X league averages, so he no doubt was paid well (roughly $40m), but judging by his salary history, he was paid more than he was worth later in his career, as his overall OPS (on-base % plus slugging %) was slightly above league averages for when he played. Somebody overpaid for that one year. It happens a lot in many facets of the economy and is a decision trap known as recency bias. It is why well-researched, careful, unemotional analysis matters or analytics have infiltrated the sports world so greatly because sports teams (remember, I am a suffering NY Jets and Knicks fan) have (or have had) the tendency to overpay for past performance.

The astute observer will note that Anderson played in the steroid era, which is relevant given that Aaron Judge’s HR total this year is likely untarnished (versus Bonds, Sosa, McGwire). Some wonder if he breaks the 61 mark, he should be considered the single-season HR record holder. And, since Judge has a historically great season during a contract year, some wonder how much he will get offered in the offseason. It is a complex problem because Judge is super talented and has a career year. Still, he is also injury prone and is not young, so some of the next contracts could overlap with a period of diminishing production. Being a fan favorite, a team leader, and a fine representative of the organization for sports fans (Derek Jeter-like) while proven ability to operate in the New York market should command a premium, but how much?

The relevance of the baseball stuff above is that when discerning skill and what to pay for the skill, we need more than one piece of information, and we need to project out possibilities. Everything should be fully transparent in the asset management game (often after some NDAs are signed). Cathie has been an investor for a long period, and her long-term track record should be revealed (absolute, risk-adjusted, versus benchmarks) to receive fees from investors (retail or otherwise). Instead of bloviating about all sorts of things (some of which she has domain experience, others not so much), and trying to raise capital in an arena (VC, where manager experience/track record and entry point matter a lot), she should put her performance into the public domain net of fees to help investors know whether she has the true sustaining skill, or just had a Brady Anderson great year, aided greatly by an outside force (steroids, or stimulus on steroids).

And so when I ran across this article, Cathie Wood (of all people) was going to launch a venture fund and open it to individual investors it kind of ticked me off. In one of my first pieces, I wrote about how her performance wasn’t all that hot given the risks she was taking, and I have shorted her fund (although I am not short now) with great success. Simply stated, I think she is broadly arbitraging a few different things in money management and the current culture (social media, the democratization of finance, etc.), and, once again, good for her. Investors can vote with their feet, but after watching a lot of hucksterism these last few years (hello NFT, much of crypto, SPACs) and knowing what I know about venture capital, I struggle to see how this is the type of manager that the retail world should be used to enter into the space if they enter the space at all.

Shameless Plug:

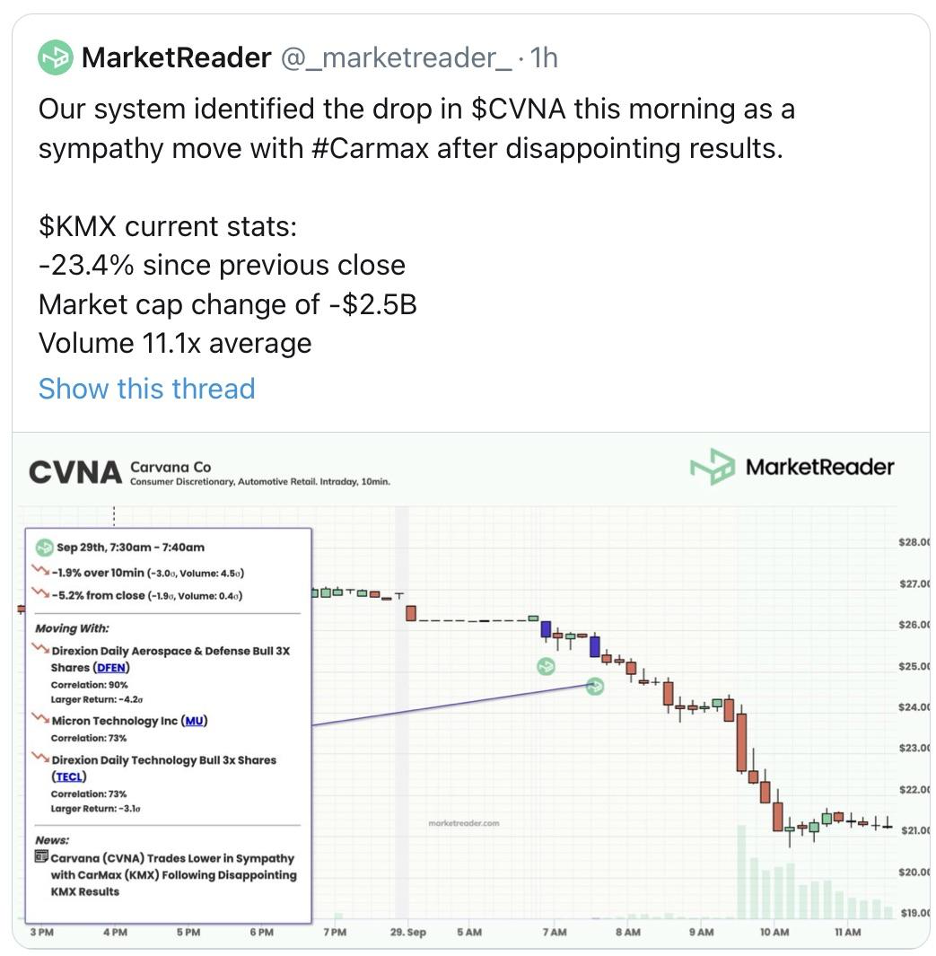

Market Reader is a company I am involved with as an investor because I believe there is a market gap for a service that can point out what is moving in real-time and put it into context. It is still a work in progress, but they just came out with a new release that is worth giving a follow.